Microplastics are very small plastic particles, less than 5 millimeters (or 1/20th of an inch) in size. They come from common items such as degraded plastic bags, synthetic clothes and textiles, some hygiene products, and cigarette filters. Research is currently being done to learn how much and what kinds of microplastics are found in four Minnesota sentinel lakes: Peltier, Elk, White Iron, and Ten Mile. So far, plastics have been found in the waters and on the bottom of the lake in the sediment of all four study lakes.

In the fall of 2020, researchers will begin dissecting two types of fish to see if there are any plastics in their guts: 1) filter feeders (cisco) and 2) visual feeders (bluegill and perch). Anglers can submit fish stomachs throughout the year for research staff to dissect and analyze for any microplastic consumption.

White Iron Lake Angler Volunteers Urgently Needed

The Research Team is ready to receive fish stomachs from anglers who want to contribute to the project! They are looking for anglers who can commit to sending 10 fish gut samples from White Iron Lake in 2020. Additional information on how to process, including stomach & intestine removal noting how to keep the organs intact, how to prepare and package for shipment, and where to ship samples is located at www.mnplastics.org in an easy how to video.

If people want a fish gut collection kit, they can inquire with Dr. Schreiner at

Samples are mailed to: Large Lakes Observatory, 2205 E 5th St., Duluth MN 55812.

More about the project: The Legislative Citizen-Commission on Minnesota Resources (LCCMR) funded the two yearlong microplastics project in 2019, and it concludes 2021. The microplastics project team is led by Dr. Kathryn Schreiner, a researcher from the University of Minnesota Duluth (UMD), and comprised of additional researchers from UMD, the Sentinel Lakes program coordinator from Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, and an extension staff from Minnesota Sea Grant. Questions about the project can be directed to: Dr. Kathryn Schreiner,

The 2017 discovery of starry stonewort in Grand Lake led to the lake association and Minnesota Department of Natural Resources rapidly mobilizing to hand-pull the infestation. This early intervention has widely been considered a success, with starry stonewort continuing to be limited to the small area near the public access where it was initially discovered.

The 2017 discovery of starry stonewort in Grand Lake led to the lake association and Minnesota Department of Natural Resources rapidly mobilizing to hand-pull the infestation. This early intervention has widely been considered a success, with starry stonewort continuing to be limited to the small area near the public access where it was initially discovered. I was lucky enough to spend this last week out on Lake of the Woods in a favorite cabin, surrounded by trees, wildlife and, of course…water. I instantly felt a sense of calm and relaxation when I got there and as each day passed, a greater sense of respect and gratitude for this lake and its surroundings. For the most part, as I kayaked and canoed along the shoreline, I noticed many properties have kept a buffer of vegetation at the shoreline. They’ve kept things wild by letting the grass grow, letting the trees and shrubs stabilize their shoreline, minimizing the artificial structures and reducing disturbance. But, our lakes need everyone to do this, collectively, in order to have the biggest impact. Those who own waterfront property really do have a unique responsibility.

I was lucky enough to spend this last week out on Lake of the Woods in a favorite cabin, surrounded by trees, wildlife and, of course…water. I instantly felt a sense of calm and relaxation when I got there and as each day passed, a greater sense of respect and gratitude for this lake and its surroundings. For the most part, as I kayaked and canoed along the shoreline, I noticed many properties have kept a buffer of vegetation at the shoreline. They’ve kept things wild by letting the grass grow, letting the trees and shrubs stabilize their shoreline, minimizing the artificial structures and reducing disturbance. But, our lakes need everyone to do this, collectively, in order to have the biggest impact. Those who own waterfront property really do have a unique responsibility.  As the season progresses and surface waters warm, thermal stratification sets in with warm, less dense waters floating on top of the deep cold waters, with little mixing between the layers. Whatever dissolved oxygen there is in the deepest parts of the lake is all that is available until lake turnover once again, in the fall. Nature is truly amazing.

As the season progresses and surface waters warm, thermal stratification sets in with warm, less dense waters floating on top of the deep cold waters, with little mixing between the layers. Whatever dissolved oxygen there is in the deepest parts of the lake is all that is available until lake turnover once again, in the fall. Nature is truly amazing.

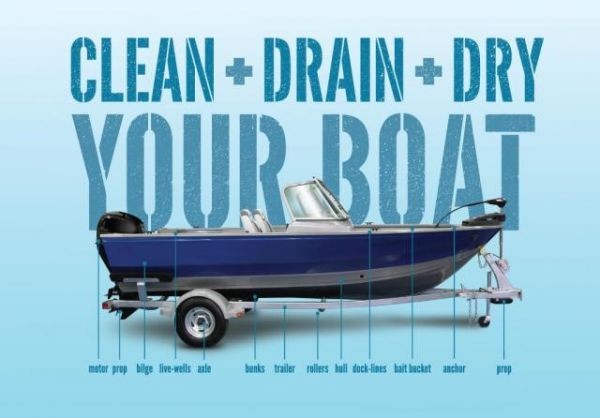

leaving a waterbody

leaving a waterbody

An April view of White Iron Lake.

An April view of White Iron Lake.

In Ontario, a person found leaving garbage on the lake can be charged under Sec 27(1)(b) of the Public Lands Act for unlawfully depositing any substance, material or thing on water or ice covering public lands (i.e., the lake). Public information and tips can certainly help – individuals who see an offence can contact the MNR tips line (1-877-TIPS-MNR; 1-877-847-7667) or Crime Stoppers (1-800-222-TIPS; 8477).

In Ontario, a person found leaving garbage on the lake can be charged under Sec 27(1)(b) of the Public Lands Act for unlawfully depositing any substance, material or thing on water or ice covering public lands (i.e., the lake). Public information and tips can certainly help – individuals who see an offence can contact the MNR tips line (1-877-TIPS-MNR; 1-877-847-7667) or Crime Stoppers (1-800-222-TIPS; 8477). The surface area of Lake of the Woods is 3,850 sq.km – where does all this water come from? By far, most of the water (about 75%) entering the lake is from the Rainy River at Fourmile Bay at the south end. In fact, the Rainy River drains a massive land area of more than 50,000 sq. km (Clark and Sellers, 2014) in both Ontario and Minnesota, with its headwaters just west of Lake Superior. To put this into perspective, the total land area of Nova Scotia is 55,000 sq km, including Cape Breton and many other coastal islands, so the size of the watershed draining via the Rainy River is immense! Other sources of inflow to Lake of the Woods include the smaller streams and rivers encircling its perimeter, rain falling directly on the lake and, when water levels are lower on Lake of the Woods than Shoal Lake, water can flow in from there as well.

The surface area of Lake of the Woods is 3,850 sq.km – where does all this water come from? By far, most of the water (about 75%) entering the lake is from the Rainy River at Fourmile Bay at the south end. In fact, the Rainy River drains a massive land area of more than 50,000 sq. km (Clark and Sellers, 2014) in both Ontario and Minnesota, with its headwaters just west of Lake Superior. To put this into perspective, the total land area of Nova Scotia is 55,000 sq km, including Cape Breton and many other coastal islands, so the size of the watershed draining via the Rainy River is immense! Other sources of inflow to Lake of the Woods include the smaller streams and rivers encircling its perimeter, rain falling directly on the lake and, when water levels are lower on Lake of the Woods than Shoal Lake, water can flow in from there as well.  What about those fish swimming around in frigid waters? Fish can survive the freezing-over of lakes because they are cold blooded, meaning their body temperature matches their environment. Colder temperatures mean a reduction in their metabolism and a slowing down of respiration, digestion and activity level; since their food supply is reduced, this is a great example of an adaptation mechanism. Cold-blooded reptiles and amphibians that overwinter under the ice survive by hibernating in the mud at the bottom of ponds or shallow bays of lakes.

What about those fish swimming around in frigid waters? Fish can survive the freezing-over of lakes because they are cold blooded, meaning their body temperature matches their environment. Colder temperatures mean a reduction in their metabolism and a slowing down of respiration, digestion and activity level; since their food supply is reduced, this is a great example of an adaptation mechanism. Cold-blooded reptiles and amphibians that overwinter under the ice survive by hibernating in the mud at the bottom of ponds or shallow bays of lakes. Kelli Saunders, M.Sc.

Kelli Saunders, M.Sc.

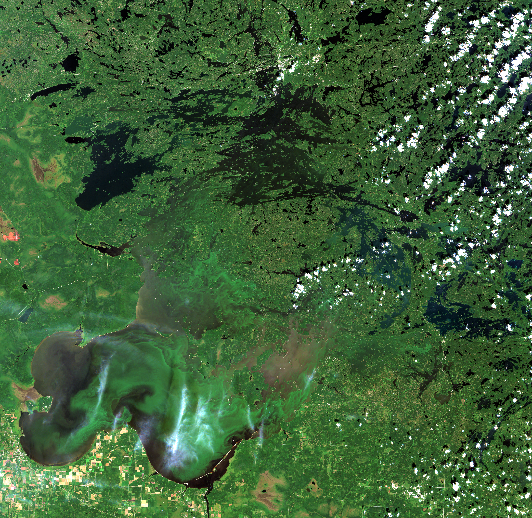

Remote sensing allows scientists to capture frequent snapshots of algal bloom conditions across Lake of the Woods in near-real-time (within a few hours of the satellite passing over), providing observations not possible using ground-based sampling alone. It provides the ability to see day to day variability of algal blooms on the lake, between-year changes in the size of blooms and timing of bloom severity and an understanding of the processes that drive blooms. How does this relate to what’s actually happening in the water, you ask? When present in sufficient quantities, phytoplankton (microscopic plant-like organisms including cyanobacteria) can cause dramatic changes in water color and form visible scums at the water’s surface that are detectable from space using camera-like optical sensors on-board the satellites. What is happening on the water can be interpreted in the satellite images over a large geographic area.

Remote sensing allows scientists to capture frequent snapshots of algal bloom conditions across Lake of the Woods in near-real-time (within a few hours of the satellite passing over), providing observations not possible using ground-based sampling alone. It provides the ability to see day to day variability of algal blooms on the lake, between-year changes in the size of blooms and timing of bloom severity and an understanding of the processes that drive blooms. How does this relate to what’s actually happening in the water, you ask? When present in sufficient quantities, phytoplankton (microscopic plant-like organisms including cyanobacteria) can cause dramatic changes in water color and form visible scums at the water’s surface that are detectable from space using camera-like optical sensors on-board the satellites. What is happening on the water can be interpreted in the satellite images over a large geographic area.